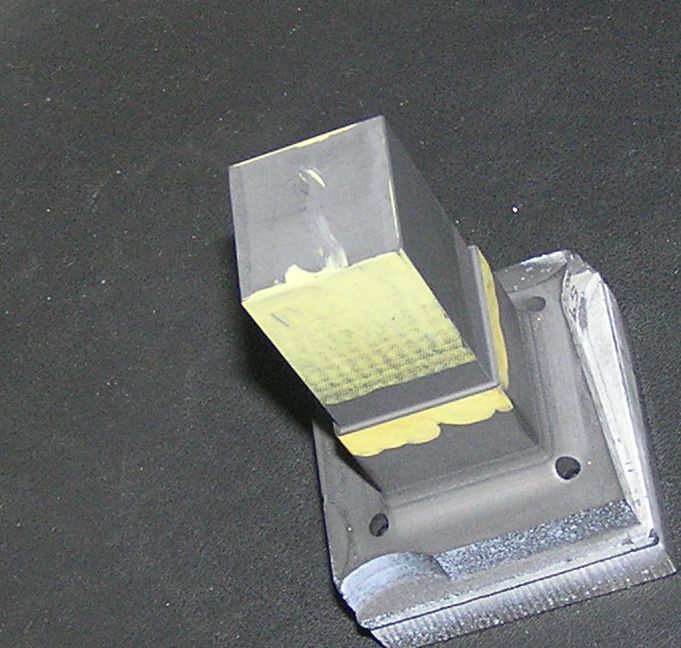

Seeing is believing. We rely heavily on sight to guide our actions. Accordingly, seeing something for ourselves is a powerful way of having us believe it. When we plan systems to control manufacturing activity, the ones that use things that we can see to guide our decisions work the best. This week I was attempting to solve an accuracy deficiency on a high RPM vertical CNC machining center. This machine is used to cut graphite to make EDM electrodes for mold making. The CAD/CAM cutter path software guided shapes, cut using diamond tipped tools, need to be accurate to better than 0.001 inch (0.04mm) on all surfaces. This shape accuracy is needed to obtain the taper needed to eject parts from the mold. 0.001 inch is a tiny distance that is difficult to see and measure. A experimental method that I call a 6 time repeat study is very effective adding visibility to the task. In this case, we machined a test shape using the CNC. After the graphite was cut we used a yellow paint marker to color all surfaces that were machined. The exact same cutting program was run again. Low and behold, one face showed uncut and completely yellow.

My machinist could not understand why I called the test a 6 time repeat study. We had only run the program twice. I indicated that once the machine flunks it is no longer necessary to run the remaining passes. Had the part been black on all sides after the first rerun we would have run the program five more times painting in between every cut to confirm that the machine consistently cuts accurately. I had originally thought that my problem was a worn spindle bearing due to the 15000 RPM cut. The actual test part only has a hint of the zebra stripe that a worn spindle bearing creates. The 6 time repeat test for metal cutting CNC machines is similar. I machine a precision bore as the test. A black Sharpy is used for coloring the bored hole between each repeat.

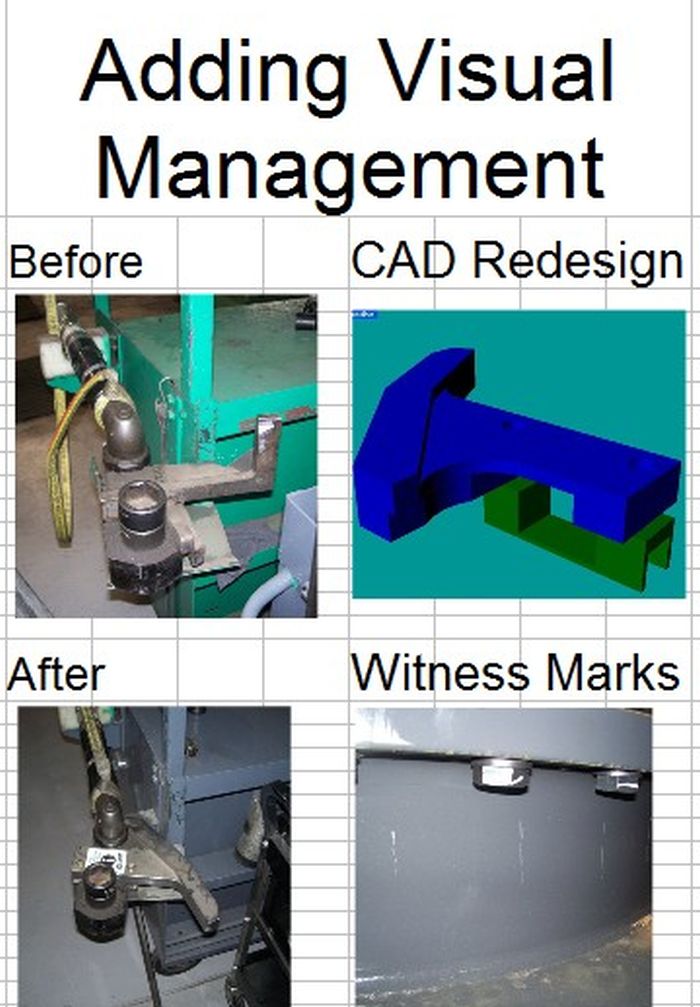

Segeo Shingo correctly taught that every manufacturing operation needs to leave a visual indication that it has been begun. He was careful to distinguish visually confirming that an operation has been begun from inspecting that it has been properly performed. His experience matches mine. For every part that is made with an operation that has been improperly performed, 9 parts are made with that same operation missed. A good example is a rough boring operation. After the part is finished machined there is no way to visually tell that the roughing bore (or drill) actually happened. A missed rough bore is a problem because the only way to achieve the desired roundness in a precision bore is to set the rough cut size so that it only leaves 0.010 inch (.4 mm) stock for the final cut. I am happy to report that the advent of CNC machining centers gives us a few more options. One of my favorite tools is to use a helix orbit to add a counter bore. I make this cut using the roughing cutter after it finishes its bore so that I can either gage or visually confirm that the cutter has not chipped. (In the pictured example, the helixed counterbore using the robust roughing cutters also protected the fragile finishing cutter from the weld located at the start of the bore.)

A classic example of a manufacturing operation that leaves no visual witness is bolt torquing. This becomes a problem when multiple bolts are needed to secure the joint. On a excavator, the turret is secured with 24 to 36 bolts depending on size. If one of these bolts is not tight, the operation of the unit will work it loose and zipper apart the entire joint. The repair, in one years time, is a $20,000 warranty cost. Confirmation of proper bolt torquing is further complicated by the locktite used to seal rust out of the thread. Checking bolt torque a day later only confirms that the locktite is working. This is where Shingo’s visual management concept fits in. Every operation needs to leave a visual witness that it has occurred. This warranty cost was eliminated by redesigning the bolt tightening wrench so that it left a mark when it was used to tighten a bolt. It became possible to visually see walking by that every bolt was tightened.

Not every application can tolerate a scratch in the paint. I have also modified open end wrenches and sockets so that they leave an imprint on the bolt head or nut when the torquing operation is performed.